The Aquincum Museum’s temporary exhibition guides visitors along the Roman Empire’s land and water routes, looking at where they ran, how they were established, who travelled on them and by what means, as well as what is left of the famous roads of ancient Rome. Interview with Dr Orsolya Láng, Director of the Aquincum Museum, co-curator of the exhibition.

Did all roads in fact lead to Rome?

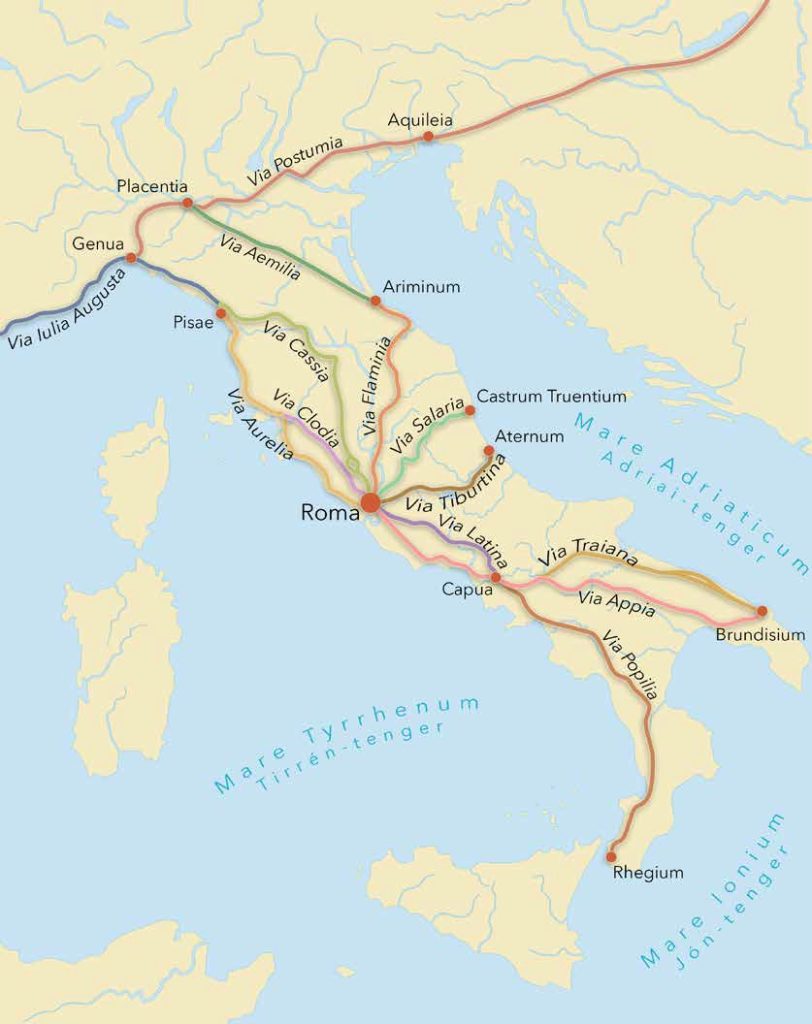

The saying ‘All roads lead to Rome’ is actually medieval, but if we look at the map of the Roman Empire, we see that the first major routes really do start from Rome. During the golden age of the Roman Empire, some 29 very important routes started from Rome alone. The total road network is estimated at 400 000 km; by then naturally roads started not only from Rome, but also from the most important provincial centres and cities. These completely covered the empire. Indeed, we can find no part of the provinces without a main road running in them.

The most important roads leading out of Rome

Without GPS and phone apps, how did ancient travellers get their bearings?

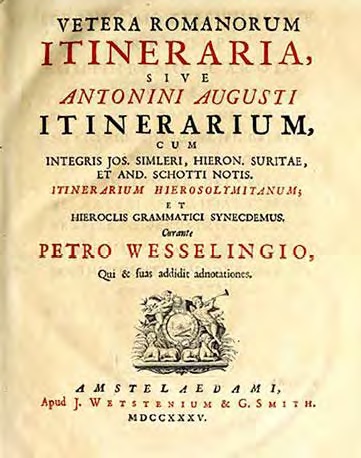

In Roman times, too, there were itineraria and maps which made it possible to plan a journey. Two of these still exist today. The first is the Tabula Peutingeriana. This is probably a summarised version of several earlier maps, and in this form it dates to the 4th century AD. Then there is the much earlier ltinerarium Antonini Augusti, which dates to the 2nd century. Both marked the main towns and the points with a horse-changing station or any kind of accommodation, they indicated the routes between them, and provided the distances in Roman miles. If someone set out on a journey, they could plan exactly which route they could take, where they could stop, and in this way it was possible to calculate how long the journey would take.

A section of the Tabula Peutingeriana with Aquincum marked. Medieval copy. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek.

These maps and itineraria were not available to everyone, of course. They were mainly for people on official business (e.g. the imperial postal service), and the military could also use them. This obviously required surveys very accurate for the time.

The 1735 edition of the Itinerarium Antonini. Getty Institute, Malibu, USA.

Was there tourism in Antiquity?

Tourism did exist in the ancient world, even if maps were not primarily for tourists. We know that there were popular ‘tourist destinations’ to which people were keen to travel – of course this meant the wealthier Romans, as travel was expensive. These included, for example, the Egyptian pyramids in particular, but also resorts where there was some kind of spa, such as Baiae in the case of Italy. Also, belonging to tourism is the religious tourism connected with various oracles or key sanctuaries. On the basis of modern parallels, these could be better described as pilgrimages. We also know that tourism existed in the ancient world, from the small souvenirs that travellers brought back from certain places.

There were also guides specifically made to meet the needs of travellers. We must mention in particular Pausanias, who in his work ‘The Description of Greece’, written in the 2nd century AD, covers those key settlements, buildings and works of art which, in his opinion, are worth seeing when visiting Greece. Pausanias’ descriptions are still used intensively in archaeological and historical research today, since much of what he saw then no longer exists or is not visible in the same form. However, the monuments that do exist today look the way he described them, so presumably his other descriptions are also accurate.

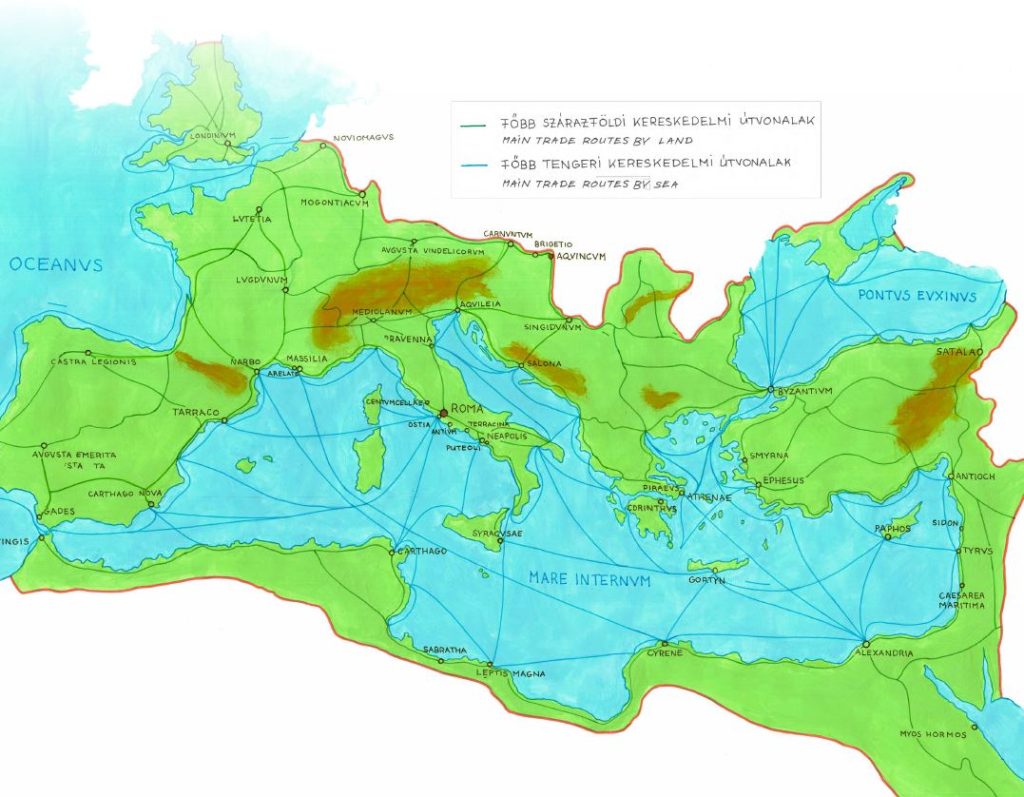

Main routes by land and sea in the Roman Empire

Then there is Strabo, who, in his Geography gives a geographically-based description of the different regions of the known world of the Roman period. This is also very useful up to this day, and was a help to travellers in those days. In addition, there are other types of guides that were helpful more in organising pilgrimages. One of these is the Itinerarium Burdigalense, which dates to the 4th century AD and basically provides a guide for Christians, describing a pilgrimage route to what is now Israel.

Where could travellers find accommodation?

Lodgings were typically roadside inns or road stations. Road stations typically offered accommodation to people on official journeys, and the inns were usually also used by people on official journeys, or possibly by traders. These had small rooms – opening from a central corridor – with very simple furnishings: a bed, perhaps a small bench, and an oil lamp. In addition, food was also available: usually a one-course dish, cheese, bread, ham. Other services could also be available. We have an inscription from Aesernium (modern Italy) where a dialogue between an innkeeper and a traveller was recorded by the stonecutter. The innkeeper lists what services the traveller had used: how much the wine cost, how much the food cost, how much hay for the mule cost, and how much the girl cost. Here, apparently, ‘other’ services were also available, which was an accepted and common thing in the Roman period.

Room at a Roman inn. Photo from the exhibition.

In many cases, especially in towns, there would also be a bath suite attached to these inns, or at least there would be a bathhouse nearby. However, such inns could be found not only on the outskirts but also within the towns. In the case of the Aquincum Civil Town, we know of at least two buildings that functioned as such inns. One was located in the zone of the southern town wall and gate, the other in the zone of the northern town wall and gate. In Aquincum we also know of such a building outside the walls. On the Danube bank, in the zone of the former Limes road, a building that would typically have had such a function was excavated a few years ago. Very interesting and rich wall painting finds were uncovered in it; it is typical of the inns in the towns that they had rooms with painted walls.

Did Aquincum and its surroundings have an advanced road network?

Yes, Aquincum and the area around it had a very developed road network. We need to remember that Aquincum was the capital of the province of Lower Pannonia from AD 106, and as such it was also an administrative and military centre, so it was very important to have a proper road network, on which the military could move around easily, and which could also accommodate the traffic of the administration and trade without any problems. The road network built in the case of the Aquincum settlement complex is still largely in place and usable today. There are many main roads here in Óbuda and in the 3rd district in general that are based on Roman foundations or follow the path of Roman roads: e.g. Szentendrei Road, Vörösvári Road, Pacsirtamező Street and Bécsi Road.

Aquincum from above

But on the Pest side of Budapest, too, there are roads that likely had a predecessor in Roman times, or at least routes that were used in historic times. The path of Kossuth Lajos Street – Rákóczi Road – Kerepesi Road – Veres Péter Road is an east-west route through which barbarians could trade with the Roman Empire in peacetime, and which also served as a military route in less peaceful times. Some believe that Váci Road may also date back to Antiquity.

What role did water routes play in the Roman Empire?

In the Roman period, there were basically two types of water routes: sea routes and river routes. The use of the sea routes was very important, since the grains that were predominantly brought to Rome were grown in what is now Egypt and Libya, and a significant part of the olive oil and fish sauce – which was used in huge quantities for cooking – was also produced in North Africa, mainly in Morocco.

If we take into account the results of underwater archaeology and other written sources, we can draw a very dense network of water routes in the Mediterranean. Previously it was thought that transport was mainly done by coastal routes, but research in recent years has clearly shown that there was plenty of open-sea navigation. The sailing season at sea was from March to October; in the very early spring and in the winter, there was no shipping due to sea storms, except when absolutely necessary. There were, however, no passenger ships, so if people wanted to get from one place to another by sea, they would have to pay to hop on board a ship used for trade.

In addition to maritime trade, the use of river routes was also very important in Roman times. In the case of Europe, the Rhine and the Danube not only provided trade or transport, but were themselves the frontier; hence, in times of war, troops could be moved on them by military riverboats. The primary role of the river was to supply the various troops stationed along the rivers. Most of the legionary fortresses and smaller military bases were located primarily along the borders, at least until the 4th century.

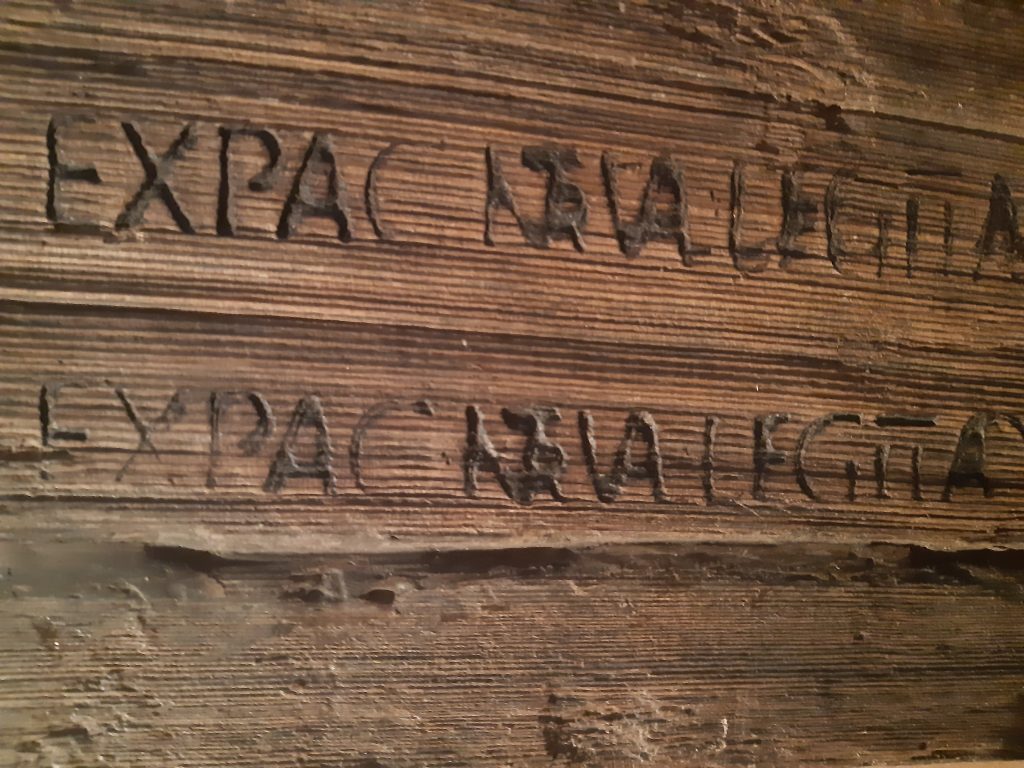

Secondarily-used barrel stave (mid-2nd century AD, Aquincum Civil Town). The inscription means: “Foodstuff by contract for the hospital of the legio II Adiutrix”

Not only foodstuffs but also other commercial goods were transported by river, such as ceramic vessels and other items that could be used to supply either the military or the civilian population. It is also no coincidence that one of the largest pottery workshops in Aquincum, almost an industrial site, was located on the Danube – east of the Civil Town, on the site of the former Gasworks – where goods could be transported on the Danube. We can find pottery vessels made in this workshop even in what is now Serbia.

Zoltán Quittner

The exhibition All roads lead to Aquincum can be visited until 30 December 2022 at the Aquincum Museum.

Curators of the exhibition: Dr Orsolya Láng, Katalin Lengyelné Kurucz, Nikoletta Varga, Barbara Hajdu, Dr Paula Zsidi