In episode five of our online exhibition "Ingenious inventions – Innovative ideas", we'll take a glimpse into the lives of everyday heroes from the ancient history of technology!

I set out but was attacked on the way by brigands who robbed and wounded me. I escaped, came to Saldae and met Clemens, the governor. He led me to the mountain, where he lamented about the tunnel construction work gone awry. They thought the construction would have to be abandoned as the two tunnels were already dug longer than the width of the mountain. It was clear that the excavation diverged from the plotted course. The upper tunnel segment [on the side of the mountain where the water would enter] turned right, i.e. towards the south, and the lower segment [where the water would leave], too, turned right, i.e. towards the north. Both construction teams missed the way, as they did not follow the line. The precise path was marked out over the mountain with stakes from east to west. . . . I then divided up the tasks, so that everyone knew at which part of the tunnel they had to work. I called in marines and Gaulish auxiliary troops, who would compete with each other in digging the tunnel from both sides and so they met in the middle of the mountain. I was the first who made the survey, organised the construction of the aqueduct, and carried it out according to the plans that I had given Petronius Celer, the governor. With the water channelled into the aqueduct, the governor Valerius Clemens dedicated the finished structure.

The passage comes not from an Asterix comic, but from real life. Sometimes, in addition to the scientists presented in earlier episodes of our online exhibition, we also get to glimpse into the lives of the everyday heroes of the history of technology. The above story comes from the epitaph of the ‘levelling engineer’ Nonius Datus which reports the tunnelling works fiasco.

Plotting the path of an aqueduct with a huge spirit level, the so-called chorobates (drawing by Éva Murakeözy)

Our story begins in AD 138, in the North African town of Saldae. The townsfolk decide to build an aqueduct in order to collect water from a cluster of springs 21 km away. For drafting the plans they receive – through the provincial governor – an aqueduct building specialist from the military unit stationed in the neighbouring province of Numidia. He visits the site and produces the plans. Construction, however, only begins some ten years later. At that point Nonius Datus returns, plots the line of the aqueduct, supervises the work, but, on account of a grave illness, has to return home.

The work continues in his absence, but something goes amiss. A 428 m stretch of the aqueduct is meant to run through the belly of a mountain. In line with the plans of Nonius Datus, the workers start tunnelling on either side of the mountain, planning to meet in the middle. Both teams, however, depart from the plotted course and dig in different directions. By the time they realise their error, they are so far apart that they consider abandoning the aqueduct altogether.

By now a veteran, Nonius Datus returns – going through quite an adventure on the way – successfully corrects the mistake and completes the work using soldiers. The governor then dedicates the aqueduct in 151. After all this, it might not come as a surprise that Nonius Datus chose to display on his memorial the figures of Patientia (Endurance), Virtus (Courage), and Spes (Hope).

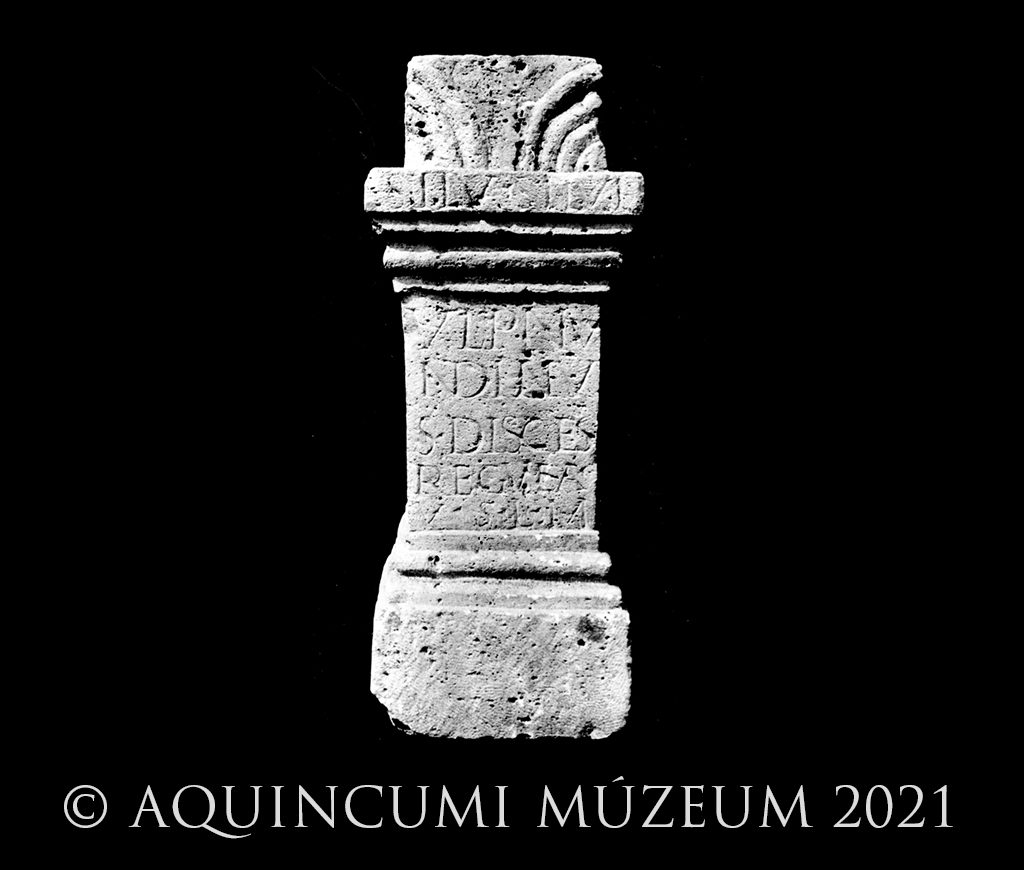

The altar of Ulpius Nundinus, a ‘specialist working with a ruler’, from Aquincum (photograph by Péter Komjáthy)

While no story with such turns is known from Aquincum, the engineer Ulpius Nundinus who set up an altar at the springs of the Aquincum aqueduct might have faced similar troubles. The aqueduct of Aquincum was built during the early-2nd century by the engineers of the Legio II Adiutrix, which was stationed here. The water was brought from the cluster of springs at the modern-day Roman Lido to the legionary base at what is now Flórián Square in Óbuda. The aquaeductus was presumably remodelled a number of times. This was necessary due to the increasing demand— water would also have to be supplied to the Civil Town. And since already during the Roman period cracks were appearing on the structure – built across a soggy and marshy area – the aqueduct had to be reinforced and repaired.

Ancient bronze carpenter’s rule, from the assemblage found at Szél Street in the Third District of Budapest (photograph by Péter Komjáthy)

Ulpius Nundinus is referred to as discens regulatorum on his inscription, i.e. a ‘specialist working with a ruler’. He set up the altar to the god Silvanus – at the source of the aqueduct in what is now the Roman Lido – in fulfilment of his vow made presumably during the construction of or repair work on the aqueduct. In his work, he too presumably could not do without endurance, courage and hope.

Roman spring house with an altar at the modern-day Roman Lido (image by Zsolt Fodor)

Written by: Dr Gabriella Fényes

Click here to read the other entries of our online exhibition.